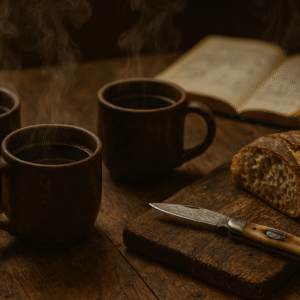

I kept trying to write this one like one of Anna’s field reports and it kept breaking on me. Meals don’t fit into “conditions, actions, results.” They just happen, and then months later you still remember the chipped bowls at Mel’s, the tavern stew in the Market Ward, the buns at Klebbers, and who was across the table when you ate them.

This entry is me tracking the bowls and cups that stuck: chowder in East Bay when the observatory stopped being my private project, stew in Skelderheim when my body finally believed that world could feed us, coffee in a quiet shop while Myles tried to explain what we had actually done to the array. It’s about food as grounding, windows as a way to watch both worlds, and the way Charles, Anna, Todd, and Myles change when there’s something warm between their hands and no one is in immediate danger.

PRINT THIS CHAPTER AND BUILD YOUR OWN BOOK!

This entry is available in two printable versions: a half-letter booklet and a full-page US Letter version. If you want to fold and staple your own booklet, you can find step-by-step printing and assembly instructions at:

https://charlesmandrake.com/create-your-book/